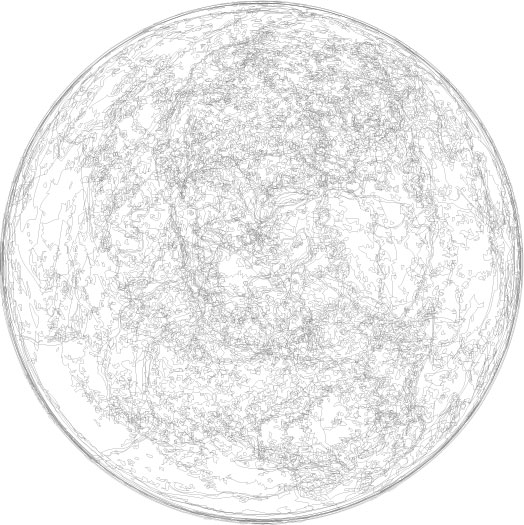

![]() Tímasetning - blek á pappír, 50X70cm - María Sjöfn, 2024

Tímasetning - blek á pappír, 50X70cm - María Sjöfn, 2024

(English below)

Breiðdalssetur, Rannsóknarsetur Háskóla Íslands á Breiðdalsvík

Tímasetning er sería verka sem ég vann í samstarfi við Þórbergssetur, Breiðdalssetur og Rannsóknasetur Háskóla Íslands á Breiðdalssvík. Þar skoða ég skrif Þórbergs Þórðarsonar um hið fjölbreytilega lífríki í Suðursveit með tengingum við rannsóknir jarðfræðingsins dr. George Walker, sem vann að og skrásetti jarðsögu Austurlands.

Verkið er hluti af myndlistarsýningu Nr. 5 Umhverfing og er ferðalag um sveitarfélagið Hornafjörð og er varðað listaverkum eftir 52 myndlistarfólk sem hefur tengingar við svæðið.

Vefsíða: https://www.academyofthesenses.is/

@academyofthesenses

#umhverfing

Sérstakar þakkir til Þórbergs Torfasonar, Maríu Helgu Guðmundsdóttur, Þórbergsseturs, Breiðdalsseturs, Rannsóknarseturs Háskóla Íslands á Breiððdalsvík, fjölskyldu, vina og vandamanna.

1

Mest fannst mér spennandi að horfa á þá í sólskini seint á degi, þegar skuggarnir af þeim voru farnir að gera sig stóra. Þessir stækkandi, svörtu skuggar, sem eins og héngu við steinana og mjökuðu sér alltaf undan sólinni, eins og þeir vildu ekki vera í birtu, gerðu þá meira lifandi og ískyggilega og vöktu í manni kitlandi hroll, ef maður horfði nógu vel á þá.

2

Þarna úr þessu klettabelti hefur þessi steinn komið. Þar hefur hann verið búinn að eiga heima í milljónir ára,“ — ég hafði heyrt sagt, að fjallið væri svo gamalt — og aldrei getað hreyft sig allan þennan tíma, og loksins eftir öll þessi ár hefur honum tekizt að losa sig úr þrælahaldi fjallsins og hefur hlaupið hingað niður í brekkurnar til okkar, svo að hann gæti lifað eins og frjáls einstaklingur.

3

Ég sá á útliti steinanna, að þeir voru á ólíkum aldri. Sumir voru unglegir. Þeir voru næstum strákalegir og sumir stelpulegir. Það var eins og væri mikil hreyfing í þeim, og það var glatt yfir þeim og nýlegur blær á útliti þeirra.

Aðrir báru það utan á sér, að þeir voru mjög gamlir. Þeir voru ellilegir á litinn. Það var dauft yfir þeim, og hreyfingin í þeim var hæg og þunglamaleg.

Í brekkunum fyrir ofan Breiðabólsstaðarbæina voru nokkrir stórir steinar. Þeir voru ekki mjög stórir, og sumir voru minni en aðrir. Þeir stóðu þar á víð og dreif.

4

Gaman væri að vita, hvenær þessi steinn hefur komið, hvaða ár, í hvaða mánuði og hvaða mánaðardag, hvaða dag í viku, hvort heldur á degi eða nóttu, yfir hvaða kennileiti sólina bar þá eða sjöstjörnuna, hvaðan úr klettunum hann kom, hvort heyrðust miklir skruðningar, þegar hann var að koma, hvort sást mikill reykur eftir hann uppi í klettunum, þegar hann var að hoppa niður, hvort sáust djúp för eftir hann í brekkunum, hvernig veðrið var...

5

Sný hausnum í hendingskasti á móti skriðunni. „Hvert í sjóðbullandi! Nú sé ég bara ekkert, enga skriðu, engan stein, allt í svörtum blettum. Þetta hlýzt af sólinni. Nú er ég alveg búinn að missa af því. Og vera búinn að hafa sona mikið fyrir þessu! Jesús minn!“ Ég kreisti aftur augun og glenni þau upp á víxl og bölva blettunum. „Jæja, ég er að sjá soldið betur. Blettirnir eru að þynnast. Nú sé ég allar brekkurnar, nú skriðuna. Nú sé ég alveg vel.“ En steininn sé ég hvergi, hvernig sem ég hamast með augunum á skriðunni. „Hann hlýtur samt að vera þar. Ekki hefur hann getað farið neitt. Það er bara ekki rétt hjá mér, að hann byrji að sjást á hádegi, ekki akkúrat á hádegi, ekki á okkar hádegi. Þarna sérðu, — að hugsa ekki nógu nákvæmt, að rannsaka ekki, að trúa á hérumbilið!

Nú ætla ég ekki að horfa á sólina fyrr en strax eftir, að ég er búinn að sjá steininn.

6

En ég gat aldrei sjónað út með vissu, úr hvaða klettabeltum steinarnir voru komnir, hvernig sem ég reyndi. Og þess vegna urðu djúpið og víddin og hljómarnir aldrei nógu hrein innan í mér.

Ég hafði horft á þessa steina, síðan ég mundi eftir mér. Þeir gáfu brekkunum heimalegt líf eins og fólkið bænum. Og þeir voru orðnir miklir vinir mínir.

7

Ég á einkennilegan stein, hann á vindský, sem kannski verður ekkert úr. Ekki er hann farinn að rjúka austur á Mýrum ennþá. En það er allt annað að góna á vindský en að góna á stein, þó að hann sé furðulegur. Á vindský góna allir, og það getur verið gagnlegt upp á allt, sem getur fokið. En á stein gónir enginn nema ég, og það kemur engum að notum. Þess vegna verð ég hlægilegur. En það verður enginn hlægilegur fyrir að góna á ský, af því að það getur verið gagnlegt, og það er ekki kallað að góna, heldur að horfa.

8

Það var eitt við þennan stein, sem gerði hann furðulegan og ólíkan öllum steinum öðrum, og nú ætla ég að segja það, þó að það sé ótrúlegt. Hann var alltaf ósýnilegur nema í sólskini og sást þó aldrei í sólskini fyrr en sól var komin um það bil í hádegisstað. Eftir það sást hann allan daginn, meðan sól skein á hann. En undireins og sólsett varð þarna uppi í Mosunum eða ský dró þar fyrir sólu, þá varð hann aftur ósýnilegur.

Það voru þessi hamskipti steinsins úr ósýnilegri veru í sýnilega og aftur í ósýnilega í björtu, sem gerðu hann merkilegri en alla aðra steina í fjallshlíðinni, kannski í öllum fjallshlíðum í heiminum.

Bio

María Sjöfn vinnur í mismunandi miðla og oft með náttúruleg fyrirbæri og skoðar samband manns og umhverfis sem taka á sig mynd sem innsetningar, í þrívíð form sem skúlptúrar, video-innsetningar og teikningu.

Í verkum sínum fjallar hún um fjölþætta skynjun umhverfisins með innsýn í innra og ytra samhengi rýmis og efnis. Hún er að kanna snertifleti manns og náttúru á gagnrýninn hátt í marglaga þekkingarsköpun og skoðar myndmálið sem á stundum veitir ný sjónarhorn.

Hún lauk M.A. gráðu frá Myndlistardeild Listaháskóla Íslands árið 2020 og M.A. diplóma gráðu í listkennslufræðum árið 2014 frá sama skóla.

vefsíða: http://mariasjofn.net

@mariasjofn

Timing - ink on paper, 50x70cm - María Sjöfn, 2024

Timing is a series of works that I made in collaboration with Þórbergsetur, Breiðdalssetur and the Research Center of the University of Iceland in Breiðdalsvík. There I look at Þórbergur Þórðarson's writings about the diverse biosphere in Suðursveit with connections to the research of the geologist dr. George Walker, who worked on and documented the geological history of the East.

The work is a part of an art exhibition No. 5 Around and is a journey through the municipality of Hornafjörður and is a path of artworks by 52 visual artists who have connections to the area.

https://www.academyofthesenses.is/

@academyofthesenses

#umhverfing

Special thanks to Þórbergur Torfason, María Helga Guðmundsdóttir, Þórbergssetur, Breiðdalssetur, family and friends.

1

I found it most exciting, though, to look at the rocks in sunshine late in the day, when their shadows had started to lengthen. It was as if these black shadows hanging around the rocks, growing bigger and bigger as the sun slowly descended, didn't want to be in daylight, and this made them more alive and ominous, rousing in you a titillating shiver of horror if you watched them closely enough.

2

So it's from this crag belt that the rock came. It'd had its home there for millions of years'—I'd heard said that the mountain was that old—and could never move for all that time, until finally, after all these years, it had succeeded in freeing itself from the bondage of the mountain and hurtled down here to our slopes so it could live as a free individual.

3

I saw from the appearance of the rocks that they were of differing ages. Some were young-looking. They were almost boyish, and some girlish, it was as some eirlish, it was as though they were lively and happy in their movements and with freshness in their looks.

Others bore the signs of being ancient and were aged in colour. There was something dull about them and their movements were slow and cumbersome.

On the slopes above the Breiðabólstaður farmsteads were some large stones and rocks. They weren't very big and some were smaller than others. They were scattered around here and there.

4

It'd be really nice to know when this rock had arrived, what year, what month and day of the month, what day of the week, whether during the day or at night, over which landmark was the sun or the Pleiades located then, from where in the crags did it come, if any great rumbling was heard when it was com-ing, whether there was much of a dust cloud to be seen in the crags when it came bouncing down, whether it made deep marks in the slopes, what was the weather like...

5

I turn my head towards the scree in a trice. 'What the heck! Now I can't see anything, no scree, no rock, everything just black blotches. That's the sun blinding me. Now I've missed the moment completely. And I've put so much effort into this! Jesus!' I screw my eyes tight and then open them wide again in turn and curse the blotches. 'Well, I'm beginning to see a bit better, the blotches are thinning out.

Now I can see all the slopes, and now the scree. Now I can see quite well? But I cannot see the rock anywhere, no matter how much I strain my eyes at the scree. 'It must be there, nonetheless. It can't have gone anywhere. I've just got it wrong, thinking it started being visible at midday, not exactly at midday anyway, not at our midday. That's just it, you see—not thinking precisely enough, not investigating things, believing only in the more-or-less!

Now I'm not going to look at the sun until immediately after I've seen the rock.

6

But I could never work out visually for sure from which crag belt the rocks hailed, however hard I tried. And that's why the deep, all-embracing resonance within my innermost self never rang purely enough.

I'd been looking at these rocks for as long as I could remember. They gave a homely life to the slopes in the same way folk give life to the farmstead. And they'd become my great friends.

7

Now he's also gaping, me at a strange rock, and he at scurrying clouds, which may yet perhaps turn into nothing. He still hasn't dashed off eastwards to Mýrar yet. But it is one thing to gape at cloud formations and quite another to gape at a rock, even though it's an extraordinary one. Everyone gapes at cloud formations, for that could be useful in connection with everything which could be blown away. But no one gapes at a rock except me, and that's of no use to anyone. That's why I'll be seen as ridiculous. But no one is thought ridiculous for gaping at clouds, because that can be useful, and it's not called gaping either, but being on the look out.

8

There was one thing about this rock which made it amazing and unlike any of the other rocks, and I'm now going to tell you why, even though it's unbelievable. It was always invisible except in sunshine, and even then it couldn't be seen until the sun reached around the midday mark. After that it was visible all day while the sun shone on it. But as soon as the sun went down on Mosar, or clouds covered the sun, it became invisible again.

It was this daylight metamorphosis of the rock from an invisible into a visible being, and then into an invisible one again, which made it the most remarkable rock in the mountainside, maybe of all the mountainsides of the world.

Bio

María Sjöfn’s artistic practice explores forms of natural phenomena and the nature of relationships between human and non human life. Her works often take the shape of installations, sculptural interventions, video, and drawing.

Her working process begins with experimentation focusing on multifaceted perceptions of the environment, and in particular the inner and outer contexts of space and matter. She critically investigates the layered relations of the human being with its environment. When those layers are examined in a new context, visual language can create a new perspective on the matter.

María Sjöfn holds a M.A. in Fine Art from the Iceland University of the Arts (2020) and an M.A.dipl. in Art Education (2014) from Iceland University of the Arts.

website: http://mariasjofn.net

@mariasjofn

Tímasetning - blek á pappír, 50X70cm - María Sjöfn, 2024

Tímasetning - blek á pappír, 50X70cm - María Sjöfn, 2024